GATHER, STORE, RE-COMBINE

A HISTORY OF IMAGINATION

PART I

Journey into Imagination

—

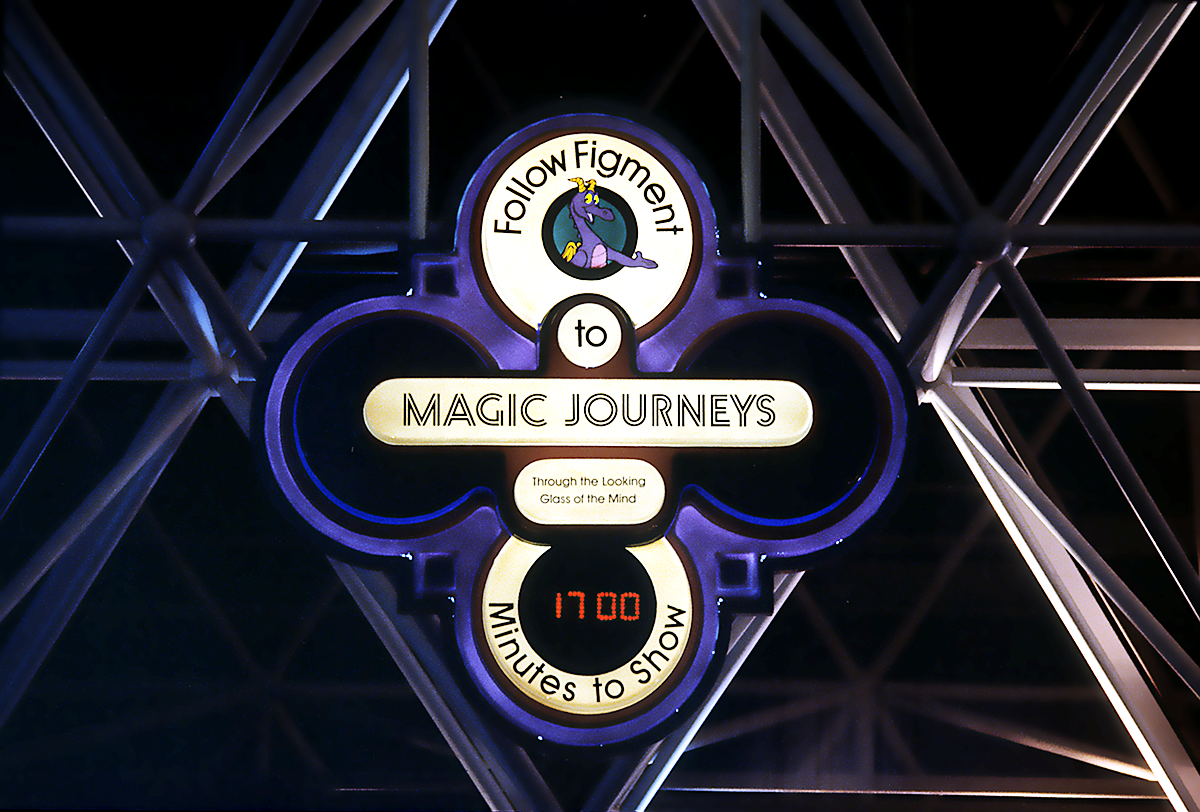

Magic Journeys

When you’re a creative entity like WED Enterprises, (now Walt Disney Imagineering), your instantly described as one the most imaginative organizations on the planet. The Walt Disney coined word “Imagineer” has Imagination in it! So to begin a history of an attraction called “Journey into Imagination” one feels like the man painting a picture of a man painting a picture. The history behind this expansive pavilion is, in many ways, describing the process for which the attraction created. A dramatization of imagination for imagination’s sake. (If you’re getting dizzy from all these circular sentences, so am I. Before we both get sick from this process of infinite regression I should stop somewhere and start our story.)

Tony Baxter, fresh-off of his first thrill attraction, Big Thunder Mountain Railroad, quickly began exploring several new concepts. One such concept would eventually become the most successful “unused” project in the history of Walt Disney Imagineering. Discovery Bay was described (by Tony himself) as “a once only place in time.” Situated on the northern-most banks of the Rivers of America it was to be the kind of place in which Mark Twain, Jules Verne, and H.G. Wells would cross-paths, and probably even call home, Discovery Bay would contain several attractions themed to technological flights of fantasy of the 19th century. The list of attractions contained in the new land were, a flight simulator on the Hyperion airship from Island of the Top of the World, an underwater restaurant where one could dine in the Nautilus while Captain Nemo plays his pipe organ, an elaborate- and thrilling – Spark Gap Electric Loop Coaster, and a carousel theater audio-animatronics tour de force “Gallery of Illusions” in which an eccentric professor shows off his latest discoveries and inventions. Unfortunately, the film Island on Top of the World, which had served as the inspiration for the land’s centerpiece attraction, the Hyperion flight simulator, “tanked” at the box office. This coupled with the extravagant plans and budget projected for this new land, all but conspired to bring about the downfall of this radical new concept. But truly great ideas never die at Imagineering, and Discovery Bay would resurface time and time again in new and unexpected ways.

Discovery Bay — Frank Armitage, 1979

A Successful Failure

Much of Discovery Bay’s “success” is attributed to the many ways it was recycled over the next two decades. The failure of this new land eventually “sparked” into the Coral Reef Restaurant at Epcot, the entirely new concept for then EuroDisney’s Tomorrowland renamed Discoveryland, and certain elements certainly would apply to the design of Port Discovery for Tokyo DisneySea.

After working on a rejected approach for The Land Pavilion at EPCOT Center, Tony quickly turned his attentions to the Kodak pavilion next door. Kodak had only one request for their Future World exhibition, “They wanted something that would be very imaginative.” So we said: “How about doing a pavilion on imagination,” Tony recalls. Beginning to develop the ideas of such a vague notion as imagination was no easy task.

“It was a fun time, and a real challenge, because we had to figure out what Imagination is. It took us six months to come up with a simple thing: “You gather, you store, and you re-combine.” […] Whether you are a writer, or a scientist, or an artist, or a teacher, or someone making a cake, it is the same thing: “gather, store, and re-combine.”

The visual metaphor Tony used to convey this principle to the audience was an inspired invention known (unofficially) as a Dreamcatcher. “Essentially, the Dreamcatcher is a giant vacuum cleaner floating through space” said Steve Kirk, art director for Journey into Imagination. The Dreamcatcher flies through space collecting sparks and storing them in its idea bag, and some of those sparks are re-combined to create something new, in the case of our story; a literal figment of imagination.

Journey Into Imagination

—

Dan Gooze, 1980

“It was a fun time, and a real challenge, because we had to figure out what Imagination is. It took us six months to come up with a simple thing: “You gather, you store, and you re-combine.” […] Whether you are a writer, or a scientist, or an artist, or a teacher, or someone making a cake, it is the same thing: “gather, store, and re-combine.”

The visual metaphor Tony used to convey this principle to the audience was an inspired invention known (unofficially) as a Dreamcatcher. “Essentially, the Dreamcatcher is a giant vacuum cleaner floating through space” said Steve Kirk, art director for Journey into Imagination. The Dreamcatcher flies through space collecting sparks and storing them in its idea bag, and some of those sparks are re-combined to create something new, in the case of our story; a literal figment of imagination.

In order to introduce Dreamfinder, Figment, and the Dreamcatcher, Tony and his team developed the use of a turntable in which the vehicles would lock into one of five identical scenes, and then unlock (like the chains in a cogwheel) to go around the rest of ride positioned around the turntable.

This “stationary” scene was a master stroke of genius that has not been repeated to this day. What is even more impressive is that this level of sophistication was achieved by a relative novice. Tony Baxter had only one completed project, Big Thunder Mountain, before Imagination and this fact is a testament to the genius of his team, and the engineers involved with this project. The rest of the Ride featured an exploration into the more creative endeavors of imagination: the [Visual] Arts, Literature, Performing Arts, Science and Technology, and finally Image Technology.

A Turntable of Controversy

Over the years many rumors have surfaced in regards to Imagination’s turntable. It is this historian’s educated opinion that most if not all of these are completely fabricated. One such rumor is that the reason for its removal was due to its in-operation on a daily basis. The original Journey into Imagination ran successfully for a period of 15 years (from 1983-1998). One wild rumor speculates that the turntable was slowly screwing itself into the ground. This would require a large amount of industrial mining equipment to be installed on the bottom of the turntable. In addition, the grinding would have cause major damage to the concrete foundations that could not be corrected in the amount of time taken for the conversion between the original and second versions of the ride.

The Beginnings of Dreamfinder

As part of the original plans for Discovery Bay the “Gallery of Illusions” was to be hosted by inventor/discoverer Professor Marvel, a “Santa Claus-type, who is wise and older and knows all great things-a great thinker” as Tony described. In one pivotal scene, the professor demonstrates his domestication of dragons. Toward the end, he’s seen holding a newborn green baby dragon. This image would later serve as the inspiration for the Professor’s sidekick.

The Birth of Figment

Although the actual events of the episode are different, Tony Baxter remembers it this way:

“I was watching Magnum PI […] on TV. He was in the garden and the butler, Higgins, had all these plants and they were all uprooted. It was a mess. Magnum had been hiding a goat out there and the goat had eaten the plants. Higgins said, ‘Magnum! Magnum! Come out here! Look at this! Something has been eating all the plants in the garden.’ And Magnum says, ‘Oh, it’s just a figment of your imagination.’ And Higgins said, ‘Figments don’t eat grass!’ I thought, ‘There is this name, the word ‘figment’ that in English means a sprightly little character. But no one has ever visualized it, no one had ever drawn what a figment is. So, here is a great word that already has a great meaning to people, but no one has ever seen what one looks like.’ So we had the name that was just waiting for us to design the shape for it.” – Tony Baxter

And thus, Figment was born, this slightly crazy, child-like baby dragon with a one-second attention span was first illustrated by Andy Gaskill, and the rest is history.

The pavilion itself started its design phase a full year later than its Future World Neighbors. However, it was still slated to be one of the opening day pavilions of the park. While the Pavilion opened, with the rest of the park on October 1st, 1982, (ok, only the Image Works was open and five days later Magic Journeys) the centerpiece attraction was “ready to go, everything was running and they made the call that the show was not perfected enough to guarantee the reliability they wanted,” Baxter said. However, considering that EPCOT Center’s opening day was (in this writer’s opinion) worst than Disneyland’s “Black Sunday,” Imagination was probably just as ready on opening day as the rest of the park. 1 Conversely, considering the unreliability of all the attractions during those first few months upper management was probably wary to add more fuel to the fire that was opening day.

With the extra time, Journey into Imagination opened on March 5th 1983. Although not without its’ own set of unique problems, most operational issues stemmed from the loading and unloading belts. Loading was performed on a stylistically beautiful but problematic curved belt. Unloading was difficult at best. Due to irregular intervals, the vehicles and the belt could not synchronize properly. Eventually, Unload was performed without a moving belt.

From the first day it opened, the Journey into Imagination was one of the most popular attractions in the park. Excluding the morning rush at Spaceship Earth, Imagination had the longest wait time of any attraction in the park. Forty-Five minute wait times were common, and the extended queue was always kept up. Ironically, the popularity of the pavilion was entirely unexpected or planned for. As David Koenig put it…

“Disney executives had always acted embarrassed about having an EPCOT pavilion devoted to a lightweight, non-scientific topic like imagination and starring a cartoon dragon. So, in publicity for Future World, Disney had always touted pavilions on ‘energy, transportation, communication and other topics for tomorrow.’ Imagination, the park’s surprise sensation, was always ‘other topics’.”

JOURNEY INTO IMAGINATION

Described by

Richard R Beard

SCENE 1

—

Flight Into Imagination

We get off to a flying start as we speed through the universe; that is what we think is happening. In our seven-passenger vehicle, we are actually moving in a large circle, with our Audio –Animatronics host Dreamfinder flying along with us in his own dream-gathering vehicle. This thirty-two-foot contraption is a wacky conglomeration of a bagpipe and blimp, furnished with oar, propellers, pulleys, and dials, a Rube Goldberg type of contrivance.

Drifting past Dreamfinder’s vehicle as it flies through the universe are animated “glows” representing ideas and inspirations. As our idea-gathering expedition begins, these glows are sucked up into the machine, which sends out puffs of smoke, jiggles, bangs, and bleeps as it stores the precious stuff of dreams. We are collecting these materials to take home where they will be recombined to make new things- inventions, stories, songs, pictures, all the cunning contrivances of the imagination. Our host Dreamfinder, a professorial type who helpfully explains and interprets what happens on the ride, seems pleased to see us and welcomes us (“So glad you could come [along]”), then turns to more pressing matters.

Notes are gathered from the air; sounds, shapes, and colors are sucked in. A combination of “horns of a steer, royal purple pigment, and a dash of childish delight” conjures up Figment, a little dragon. Figment is a spontaneous creature, full of energy and childlike wonderment. He is an ever-receptive sponge, soaking up everything he sees around him. Having never been told by an adult that he is incapable of doing this or that, he thinks he can do anything-and he is not far wrong.

“Can I image, too?” ask Figment. Can he! A passing rainbow is vacuumed up, and is transformed into a paint set for the dragon.

Ghostly shivers, goblins, and witches are ingest, to feed the darker side of the imagination, and then, in turn, the symbols of science and mathematics-prisms and gyroscopes, numbers and letters-until at last a bell signals that the idea bag is full, at least for this excursion. However, Dreamfinder assures Figment that we’ll never run out (“One new idea always leads to another”) as we cruise into the Dreamport.

SCENE 2

—

The Dreamport

In a vast, busy storeroom-representing the brain-the booty of our expedition is being unloaded into appropriate containers: jar, drawer, cartons, a boiler-cum-washing machine called the Imaginometer. The storeroom may strike us as being disordered-in the science are, the helium holder is floating away, and lead burst the bottom of a metal container-but there is an appropriate place for everything. Deep thoughts, for instance are stored in a diving bell. Lightning bolts crackle in the nature section, while the “winter days” crate chatters with cold and morning mist wafts from an atomizer. Sound effects are stored in a filing cabinet whose drawers pop open to emit an assortment of uncanny creaks, chirps, groans, and buzzes. Theatrical material is stored in a big trunk equipped with applauding hands; musical notes hum and twitter in an oversized birdcage. From the Dreamport, our ride takes us into a series of spaces where the elements that were gathered and stored are recombined, each area featuring a new twist on a familiar theme-the very essence of imagination.

SCENE 3

—

The Arts

In the realm of “Art,” Dreamfinder is painting and opalescent mural with a optic-fiber brush; farther on, a fantastically shaped, pure white forest-garden takes color under shifting caressing lights, while mirrors reflect and distort the other-worldly mindscape.

SCENE 4

—

Literature

In “Literature,” the Dreamfinder plays the console of a giant typewriter from whose volcanic top letters explode, the drift down as words into a book. Words like “tumble” of course tumble, and trembling words tremble, and once in a while a word like “genie” or “fairy” escapes and floats off to wherever genies and fairies go.

SCENE 5

—

Performing Arts

On one side of the “Performing Arts” are the accouterments of stagecraft: we hear applause, laughter, music and see the glare of klieg lights. On the other side are backstage tools: costumes, scenery, [and] makeup. Figment is still trying on costumes as the two side merge to perform what might be described as the dance of the laser beams, which flows from ballet to cancan, from precision high kicks to acrobatics. We crash through the star-studded dressing room doors and, in the twinkling of an eye, the stars turn to mathematical symbols in a clever bridge to the last area, that of “Science.”

SCENE 6

—

Science & Technology

In the center of a rotunda Dreamfinder stands at a console, manipulating and bank of screens designed to show how the arts of science and technology have given us the tools to explore realms we cannot see with the naked eye. Covering biology, botany, minerals, space, and man, Dreamfinder’s many-splendored machine has the ability to see far (the heavens) and near (microscopic organisms), to speed up (the growing process of a plant) or slow down (the movement of human muscles). Figment, eternal imp, get caught in the machinery and is stretched, compressed, slowed down, and speeded up, recovering just in time to tar in the ride’s grand finale, arrived at down a spiral of motion-picture film.

SCENE 7

—

Image Technology

In a gentle reminder that with a little imagination we can all be what we want to be, Figment poised in the center on a film reel, does his last little dance. Around him, filmed images of our indefatigable little guide, variously garbed as an astronaut, and athlete, and actor, a scientist, join him in synchronous song and dance.

The Musicology of Imagination

In the case of “One Little Spark” and the musical themes created for the ride, this is probably the first used of multiple compositions within an Omnimover style attraction. Unlike many of its predecessor attractions (it’s a small world, Pirates of the Caribbean, and The Haunted Mansion) the Journey Into Imagination does not used the “Small World Technique” (my term) of one minute looping of a singular theme in multiple variations. Instead, it employs the first ever use of an innovative technique of transitional sound effects from scene to scene. In Journey, it’s important to note where music is NOT. There is no melodic score in the Dreamport, neither in most of Literature, nor in Image Technology. The result of this ever changing soundscape, is that the attraction’s narrative is allowed to function on its own terms, instead of anchoring it to its ride system. This in-turn makes the Journey (musically speaking) a much more interesting and cinematic attraction. It also enables the attraction to reach a musical climax like few Omnimovers have achieved before or since.

The Magic Eye Theater

3-D film is nothing new to Walt Disney Productions. In 1953, long before Disneyland opened, Disney had produced the first animated films in 3D, “Adventures in Music: Melody” and “Working for Peanuts”. Both films would later be shown at the Mickey Mouse Club theater as part of “The Mouseketeer 3D Jamboree” opened in 1956. Unfortunately, this is where films in the third dimension would stop until 25 years later with opening of EPCOT Center.

Magic Journeys, is arguably the most usual and certainly one of the most forgotten films in theme park history. In fact, very little is known about the film today. Only the title song has survived in the public consciousness. Directed by Oscar® winning director Murray Lerner, the film is an exploration of the free-flowing imaginations of children. The following is the longest description/review of the film (by Karen Cure, 1983) that has survived…

Beginning with a handful of children racing across a meadow and gazing at clouds, it also brings a frothy pink-and-white cluster of spring blossoms right to the tip of your nose. The sense of proximity is so realistic that more than one visitor reaches out to touch them. Dandelion spores float through the air, turn into stars, and are then transformed into a sun whose rays become water right before your eyes. In another scene, a child’s kite changes from bird to fish to a whole school of fish, to a flock of birds, bird wings, the flying horse Pegasus, a real horse, and then a spirited steed on a merry-go-round. The brass harness ring of the carousel horse floats out to the audience, tempting all to try and catch it. Then the ring itself turns into a moon, then bats, then frightening witches and their masks and finally the Sphinx.

Noted “bloggist” and Imagineering Analysis, FoxxFur in an article describing the adult nature of the fairytales depicted in Fantasyland (Magic Journeys’ final venue) had this humorous remark…

“Accounting for Snow White, Mr. Toad’s pin up girl and hellish ending, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea’s terrifying giant squid, and nudity on Peter Pan mermaids, Fantasyland 1971 offered the highest number of attractions inappropriate for children than anywhere else on property! (If you want to go for the hat trick you have to jump ahead to 1987 when Magic Journeys played in the Mickey Mouse Revue theatre where the number of inappropriate attractions jumps from four to five because, as we know, Magic Journeys isn’t appropriate for anyone.)”

Despite its treatment of the subject matter, Magic Journeys demonstrates several technological advances in cinematography. The film’s opening and closing titles were the first to used computer generated images in 3-D. In order to receive greater clarity of the image, the film was also shot at a high 36 frames-a-second (rather than the standard 24). Most importantly, the film was the first to use the Walt Disney Productions’ “Disney 3-D Camera Rig.”

Disney 3D 101

The key to three dimensional (3D) photography is the successful approximation of human stereoscopic sight. In order to correctly accomplish this, two cameras must be set 21/2 inches apart. In addition, when projected the images must be correctly separated so that only the right eye will see the right image and only the left eye will see the left image. The problem with two cameras shooting so close to each other is that the housing and mechanics of each individual camera are much too wide to shoot 21/2 inches apart. Ever since the 1950’s, camera engineers have been plagued with this very problem. During that time, 3D rigs were devised that were both elaborate and clumsy. All of them focused on not only approximating human sight, but the appearance of the eyes as well. All rigs featured cameras joined together (in some fashion) on a horizontal plane. Not only was this impractically complex, but made shooting any 3D film next to impossible. In 1980 while the EPCOT Center project was well under way, Steve Hines of Kodak was lent-out to WED Enterprises R&D to design a new method of shooting 3D films. Steve’s requirements for the new rig were as follows…

1. To have a rigid, light-weight structure

2. To support one stationary 65mm Mitchell camera and one which would be movable.

3. To have the use of wide-angle lenses of less 50mm focal length.

4. To mount the beamsplitter rigidly so it would not twist or vibrate during shots.

5. To be able to easily adjust the convergence of the cameras’ axes from infinity to 4 feet.

6. To provide easy manual or motorized adjustment of the interocular spacing without altering the setting of the convergence.

7. To provide graduated readouts of the convergence and interocular settings measured from the position of the nodal points of the cameras’ lenses.

8. To human factor the design of the rig for easy access to all control and readouts, and radius all edges for comfortable handling by the camera crew.

9. To provide fast and east attachment and removal of both cameras to the rig and of the rig to the fluid head.

“It was an ingenious concept, a triangular framework with one camera pointing straight down into a 45 degree partially silvered mirror and the other shooting horizontally out through the mirror. This “vertical” arrangement gave a narrow frontal area and could use wider angle lenses than those possible with conventional horizontal two camera systems,” said Lerner. The Disney 3D camera rig was an industry standard until after the turn of the century and the development of RealD first used in 2005 with the release of Chicken Little. In addition, some current 3D Camera’s still use the Disney Rig’s basic design.

The Musical Journey

Music is so important to just about everything, but its importance was never more so appreciated and understood by a man that ironically possessed no musical ability; Walt Disney. In Walt’s time, everything began with a song. It sets the mood and tone of any dramatic work and it can also help tell a story. (A Disney invention.) One of the reasons why Journey Into Imagination has such a hold on the its audience a decade after its closing, is the memorable music of Richard and Robert Sherman, better known as “The Sherman Brothers.” Whether it is the ubiquitously exuberant synthetic tones of “One Little Spark”, or the playfully melodic “Makin’ Memories”, to the beautifully mysterious and thought-provoking “Magic Journeys,” each song perfectly described the feeling of each attraction long after the attractions cease to exist. The creation of these three songs was described in the Brothers book “Walt’s Time – from before and Beyond”…

Our biggest creative challenge at Epcot took us on a Journey Into Imagination – the pavilion that celebrates dreams, ideas, creativity and of course, the imagination. By the time we were done, we had created three different theme songs for the ride and its accompanying shows.

“One Little Spark” is the main them performed by the pavilion’s hosts Figment and Dreamfinder. These two delightful characters are on a never-ending quest, searching the universe of the imagination for new thoughts and ideas to bring back to their “Dreamport.”

We were also asked to write a poetic song that would accompany and enhance their state-of-the-art 3-D film. We came up with the title Magic Journeys, descriptive of the boundless imagination of the human mind.

Fresh from his Academy Award winning documentary From Mao to Mozart, filmmaker Murray Lerner was assigned by [WED] to create the film. During Murray’s stay in Los Angeles, Disney put him and his family up at the Beverly Hills Hotel, just three houses away from Bob, and before long their kids became best friends.

“Magic Journeys” turned out to be one of the most imaginative songs we ever wrote – celebrating the idea of everyday sights and sounds with an almost mystic wonderment.

To create the feel of three dimensions musically, we wrote a theme for the lyric and an ever-weaving secondary them to be played simultaneously with it. Both themes would glide on a rather complex ever-changing harmonic bass line known as a “circle of 5ths.” But maybe that’s getting a little too technical…

We loved Magic Journeys, because its state-of-the–art technology was used to make the audience appreciate what might be considered a “mundane wonder” – dimensional sight. As an interesting footnote to history, the film marked the very first use of 3-D computer imaging, in a striking title sequence that in itself cost nearly half a million dollars!

The film giant Kodak, who sponsored the Imagination pavilion, wanted a song to entertain the guest as they waited to enter the Magic Eye Theater where Magic Journeys played. Kodak’s business is all about making memories. And with that thought in place, our song was on its way.

“Makin’ Memories”…accompanied a slide show featuring images that ranged from the earliest black and white snapshots to the latest innovations in color photography.

Basically, our song was a subliminal commercial pitch for Kodak – no doubt the “softest sell” in the history of singing commercials!